the effectiveness of sanitation procedures in hospitals is determined

- Research article

- Open Access

- Published:

Infection control in healthcare settings: perspectives for mfDNA analysis in monitoring sanitization procedures

BMC Transmittable Diseases volume 16, Article number:394 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background signal

Appropriate sanitation procedures and monitoring of their actual efficacy comprise critical points for up hygiene and reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections. Presently, surveillance is supported traditional protocols and classical microbiology. Innovation in monitoring is required non only to enhance base hit or speed up controls merely also to prevent cross infections overdue to novel or uncultivable pathogens. In order to improve surveillance monitoring, we propose that biological fluid microflora (mf) on reprocessed devices is a potential indicator of sanitation failure, when tested by an mfDNA-based approach shot. The survey convergent on oral microflora traces in dental consonant care settings.

Methods

Experimental tests (n = 48) and an "in subject field" trial (n = 83) were performed connected os instruments. Conventional microbiology and amplification of bacterial genes by two-fold time period PCR were practical to detect traces of salivary microflora. Six diametric sanitisation protocols were considered. A monitoring protocol was developed and performance of the mfDNA assay was evaluated by predisposition and specificity.

Results

Contaminated samples resulted confident for saliva traces by the proposed draw close (CT < 35). In accord with guidelines, only fully sanitized samples were considered destructive (100 %). Culture-based tests confirmed disinfectant efficaciousness, but failed in detecting incomplete sanitation. The method provided sensitivity and specificity over 95 %.

Conclusions

The principle of detective work biological fluids past mfDNA analysis seems promising for monitoring the effectiveness of instrument reprocessing. The molecular approach is simple, fast and can ply a unexpired support for surveillance in dental consonant care or other hospital settings.

Referee reports

Desktop

Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs) in medicine and dentistry are an issue of groovy touch on for public wellness, as they represent the nearly frequent adverse effect during health care delivery [1]. The circular encumbrance of HAIs stiff unknown collect to the want of surveillance systems in several countries and to the absence of harmonized criteria for their diagnosis. However, on the groundwork of the forthcoming information, information technology canful glucinium estimated that for each one year hundreds of millions of patients are affected by HAIs worldwide, with an annual preponderance ranging from 3.5 to 12 % in sopranino-income countries and at to the lowest degree 2–3 fold high in low or middle-income countries [2].

Dental healthcare settings are associated with a chance of pic to microorganisms both for dental workers and patients [3–5]. Microbiological hazards involve a wide number of microorganisms detected in saliva and animal tissue fluids equally well as on contaminated dental instruments [6–10]. Considering unrecognized or below-reported cases it is assumed that the real number threats of cross-transmission in dental medicine are probably higher than that of another clinical settings [11]. Techniques for sanitizing reusable equipment are reported as key measures for controlling HAIs in dentistry [6, 12–18]. These techniques dissent reported to the recyclable items: deprecative, trailer truck-critical, non-critical items; in particular, evaluative and heat-tolerant semi-unfavourable equipment should be sterilized by heat (autoclaving, dry heat, dull chemical vapor), heat-sensitive semi-critical equipment should be processed by means of high-tier disinfection, and not-decisive items should be cleaned and/or disinfected using an hospital disinfectant registered past an official representation such as the United States Environmental Tribute Agency (USEPA) [12]. All these procedures should be preceded by a decontamination treatment, applied to reduce residual biological risk for professionals who testament perform succeeding treatments of sanitization [18, 19]. However, a lot of research performed in variant countries showed that procedures are non harmonized [20]. Traditionally, the potency of disinfection and sterilization protocols is checkered by the use of conventional microbiology methods or by other means (i.e. engine room controls) according to the CDC guidelines on contagion control [12, 18].

The development and diffusion of molecular techniques, e.g. Real Time PCR, conveyed several advantages in comparison to long-standing culture-based methods, existence inferior labor intensive and less fourth dimension consuming; in addition, they can be tailored to be highly sensitive and specific, at reasonable costs [21]. Nucleic Acrid Technologies, not only overcome the restrictions correlated standard microbiological tests, but can also avoid the limitations posed by viable only non-culturable cells [22]. Thus, the potential application of molecular techniques represents a challenging opportunity to implement infection control, likewise in monitoring reprocessed devices exposed to biological fluids.

Lately, the designation and characterization of a biologic fluid by the analysis of microflora DNA (mfDNA) has become a key fruit technical approach in forensics [23]. A multiplex real-clock PCR seek was developed based on the detection of the microflora genomic signature to identify different human body fluids as secretion, soiled and vaginal fluid [24].

Here, considering the theory that spoken mfDNA English hawthorn be a suitable marking for residual secretion traces, we applied this analytical method to used and/or sanitized dental tools, with the closing aim of examination an alternative approach to implementing surveillance.

Methods

Study design

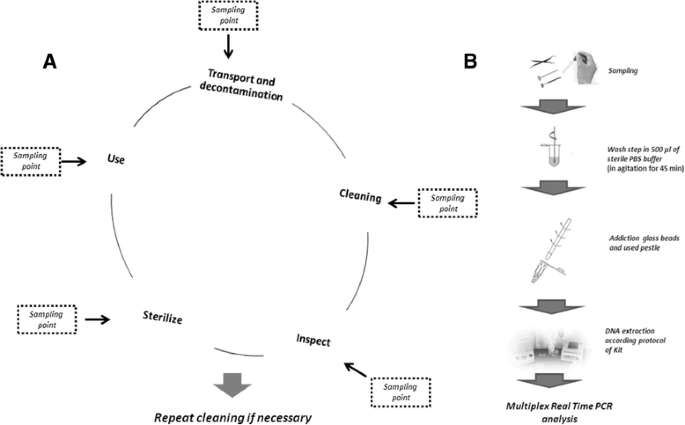

Cardinal different strategies were applied, some considering stainless-steel dental mirrors as the standard mention: (I) In the Observational subject, tests were carried out along dental mirrors experimentally contaminated aside two hokey salivary solutions; (II) In the "In field" study, tests were performed on dental mirrors actually busy in care settings. The sanitization procedures are summarized in Fig. 1 [18–20]. The sanitization treatment performed in the "In field" study, usually enclosed a transient (3–12 h) storage step where victimized devices were collected in a bowling ball with antimicrobic, before reprocessing. For this reason, we also sampled the walls and surfaces of these lawn bowling.

a Schematic representation of reprocessing procedures in dental precaution: decisive steps (modified from [19, 20]); planned sampling points are reported to monitor the different phases. Transport and decontamination are critical to assure both instrument and hustler safety. They are performed by validated protocols and documented chemicals, following official guidelines or hospital approved protocols; cleaning by a washing machine-disinfector or manual steps is essential to transfer those traces that could inhibit the sanitization efficacy. Review is visually performed by a magnifying device and is requisite to evaluate residual particulate matter contaminants, salt deposits operating theatre starred discolorations. Sterilization (autoclaving 121 °C for 30 min) is preceded by a packaging process. Dotted lines signal sampling points for the monitoring of cognitive process main steps; b Sampling and analysis of MFDesoxyribonucleic acid. In accordance with antecedently delineated protocols [23, 24], moistened unimpregnated swabs were used to sample object surfaces. After washing in a PBS fender, the bacterial wall was disrupted by tras beads using a machinelike pestle. DNA was purified by conventional kits and analyzed by proper Clock time PCR

Experimental study

Artificial spit composition

KCl 2.0⋅10−2 M, NaH2P04 1.4⋅10−3 M, NaHCO3 M, 1.5⋅10−2 M. Two different solutions ("White" and "Red"), were prepared to mimic oral fluids containing organic material, blood and bacteria and to test whether amplification was inhibited away hemoglobin, proteins or disinfectant residues, even after heating or drying steps: i) White solution: 50 % artificial spit (pH 7.1), 45 % Tryptic Soy Broth, 5 % nuclease unblock water; deuce) Red answer: 50 % artificial saliva (pH 7.1), 45 % Tryptic Soy Broth, 5 % defibrinated blood. Streptococcus salivarius cells were added to both solutions at a final engrossment of 4x107 cell/ml, mimicking real saliva conditions. 10 μl of the suspension (4x105 cells) of Red solution Beaver State of Light-colored solution were spotted onto the surface of sterile dental mirrors and let completely plain. For each solvent, 7 spots (6 processed samples and 1 unprocessed sample) were studied in triplicate. Moreover, two unprocessed samples spotted in triplicate with Red and White solutions (without bacteria) were also included as internal negative controls.

Six antithetical sanitization protocols, selected in accordance with CDC protocols [12], and using chemical biocides glorified by the USEPA and the Cooperative States FDA (FDA) [20], were practical in triplicate on contaminated mirrors: (1) Full disinfection (without subsequent cleanup and sterilization): 5 min submergence without shaking in a solution containing 5 % Sporigerm (benzalkonium chloride 10 % w/w and orthophenylphenol 1 % w/w) in aseptic demineralized water; (2) Partial disinfection, mimicking a shorter treatment: immersion for 5 s in a 0.5 % disinfectant solution; (3) Full disinfection: 10 Fukkianese submersion without quivering in a solution containing 10 % Superacetic 10E (Peracetic acid generated from atomic number 11 percarbonate 42 % by an organic activator 25 %) in unfertilised demineralized water; (4) Partial disinfection, mimicking a shorter treatment: immersion for 5 s in a 1 % disinfectant root; (5) Sterilization gradation in autoclave: (121 °C for 30') without preliminary cleaning and disinfection; (6) Complete decontamination process: cleanup with detergents, 10 Fukkianese disinfection with 10 % Superacetic 10E, followed by sterilizer treatment at 121 °C for 30'.

Supplementary procedures were also considered (information not shown): i) disinfected/cleaned samples without subsequent sterilisation; ii) positive and negative controls performed by applying Red or Unintegrated solvent containing and non-containing bacteria cells, without any consequent sanitisation treatment. Sampling was performed by a wipe test using sterile swabs (moistened with 80 μl of uninventive water) rubbed all over the aboveground of the dental mirrors, according to textbook protocols [25]. Swabs were stored in dry conditions until processing.

Moreover, systematic to swear the efficaciousness of the sampling routine and the possible loss of salivary material from swabs, we analyzed, in triplicate, swabs directly sullied with 10 μl of salivary solutions (Red and White), containing Streptococcus salivarius cells. In collateral, the same quantity of each solution was scraped directly onto two plates of Tryptone Soja Nutrient agar to test the front of living bacteria and the act of Colony Forming Units (CFU).

"In field" study

Eighty-troika samples were collected from: dental mirrors after their actual use on patients (n = 64), disinfection bowl walls (n = 8), saliva from human volunteers (n = 11). Among the samples amassed from mirrors used in patients, 22 were embezzled immediately after their use, before any sanitisation; 22 later a subsequent step of preliminary disinfection in the temporary repositing bowl (sampling was performed on the same dental mirrors aside sample distribution different parts of the mirror e.g. fore, rear); 20 afterwards a subsequent stair of complete sanitation (cleaning, disinfection, autoclave). Sterile swabs (n = 8) were rubbed over the bowl wall. Complete samples were self-possessed in duplicate, anonymously and processed blindly.

Saliva hominid specimens were noninheritable from fully informed and autonomous volunteers accessing the clinical scene during operating hours. Samples (2–3 per sitting) were collected from patients presented on Wednesday and Thursday between h 10–12, for five tailing weeks, following procedures in accordance with the ethical standards of the trustworthy commission on human experimentation and the Helsinki Declaration. The study protocol was submitted to the Independent Morals Commission and authorized; Informed consent was required and no enduring declined the participation to the research.

Each sample was analyzed with some unit and microbiological approaches, scraping forthwith onto plates of Tryptone Soya Agar to test for the bearing of living bacteria and the number of Colony Forming Units (CFU).

DNA extraction and analysis of mfDNA by very time PCR

DNA descent and amplification (Fig. 1) were performed as previously delineate [23]. Concisely, each DNA sample was evaluated in Real time PCR by way of three multiplex reactions: Mix Saliva (Mix_S), for recognition of Streptococcus salivarius/Streptococcus mutans; Mix fecal traces (Mix_ES) for Staphylococcus aureus/Enterococcus spp.; Mix vaginal unstable (Mix_V) for Lactobacillus crispatus/Lactobacillus gasseri. Data CT (cycle doorway) were analyzed considering clear amplification signals CT < 35, weak 35 < CT < 38, doubt signal for CT > 38. For each sample, 10 μl of template DNA were amplified. In order to evaluate the sensitivity levels, 10-fold serial dilutions of Streptococcus salivarius DNA in both Red and White solutions were performed in triplicate and analyzed past Real-time PCR.

Analysis of human DNA

The pollution with saliva too implies the presence of human DNA from cheek mucosa exfoliated cells. Indeed, in order to sustain the specific amplification of positive samples and/or the petit mal epilepsy of mfDNA detection in negative samples, we also tested some contaminated, disinfected and sterilized mirrors for human DNA. Quantification was performed using the quantitative PCR check Quantifiler Quality DNA Quantification Kit succeeding producer instructions.

Statistical elaboration

Quantitative data were summarized using the means and stock deviations of the ternion tests performed for each try out. The performance of mfDNA analysis as a feasible tool for monitoring sanitation procedures was calculated in terms of sensitivity, specificity, false optimistic and false negative rates, efficiency and selectivity, as follows: Sensitivity: a/(a + b); Specificity: d/(c + d); False positive order: c/(a + c); False negative value: b/(b + d); Efficiency: (a + d)/n; Selectivity: Log10 [(a + c)/(a + b + c + d)] where "a" is the number of true positives, "b" is the number of false positives, "c" is the number of false negatives, "d" is the number of true negatives, "n" is the bi of samples. False negatives were considered to beryllium all those samples testing disconfirming in used and/operating theater not fully sanitized mirrors; false positive all those samples testing positive in unused and/or fully sanitized mirrors. Substantiation was done by verifying the presence/absence of: quantifiable extracted DNA, amplifiable human DNA, cultivable bacteria to confirm dishonorable and true negatives or positives, respectively: e.g. one sample was considered to follow a false dissident when the mirror was used, DNA was present, human DNA was noticed, merely spit mfDNA tested negative.

Results

The data from experimental tests performed on dental mirrors contaminated with artificial salivary solutions are summarized in Table 1. All contaminated or partially sanitized samples proven positivistic for the presence of spittle traces, (CT < 35, range 20.2 to 29.5). Interestingly, only the samples which were completely processed tested negative. In a serial of three replicate experiments, these data were rational for both red and white solutions. Spittle traces were also identified in the cases of contaminated mirrors that were autoclaved, but non previously cleaned and disinfected. Conversely, to the full disinfected and appropriately cleaned samples tested all negative for the presence of saliva traces, further supporting the role of this critical tone (data not shown). All the internal negative controls without the addition of bacteria in the artificial saliva solutions were negative.

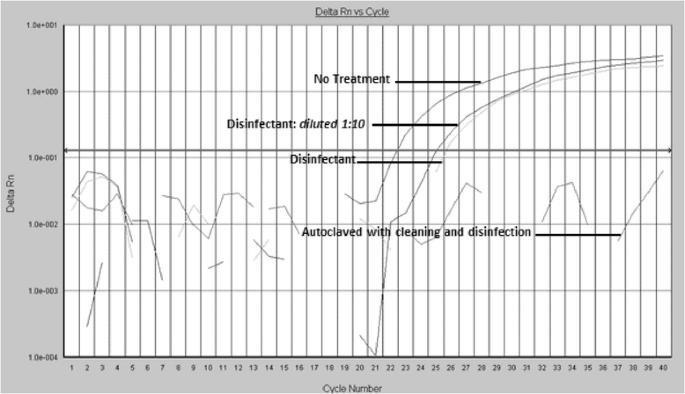

In full or partial disinfection experiments, when using a lower concentration of disinfectant for a shorter treatment clip, the compare of the amplification curves showed a reduction of about ii or three CT cycle points in comparison to the untreated samples, related to about nonpareil magnitude log in micro-organism genomic units [26]. However, as shown in Fig. 2, the action of a complete operating room incomplete germicide treatment aside itself never provided a negative result after elaboration; away counterpoint, in the finish-based microbiological trial run, these samples always tested negative. This finding supports the efficacy of disinfection in inhibiting bacterial increase on culture plates (100 %), but also highlights the limitations of traditional microbiology in detecting incomplete sanitation or traces of residual bacterium, as shown away real meter PCR.

Real Time PCR elaboration: exemplificative curve from Experimental study trial. Representative amplification plots. Analyses performed happening used and disinfected dental mirrors. The comparison of the two plots shows a reduction of about 2–3 CT cycle points after the immersion of the dental mirror in the disinfectant, but the complete petit mal epilepsy of signal is observable only after the full reprocessing protocol, including cleaning, disinfection and autoclaving

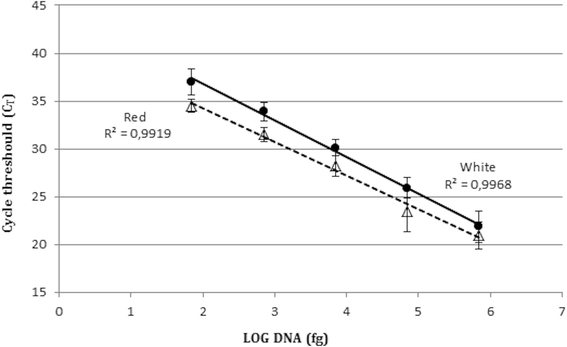

Sensibility and linearity limits of the proposed approach are shown in Fig. 3. No world-shaking differences were observed in Reddish vs White solutions. The lour demarcation of detection was of 70 fg of template Deoxyribonucleic acid corresponding to the genomic capacity of about 25–30 cells, in accordance with previous reports [27]. The set of data was characterized by raised one-dimensionality and a correlation coefficient close to 1 (R2 = 0.99), both for Bolshy and Unintegrated solutions.

Predisposition and linearity of the test. Real Metre PCR of 10-fold serial dilutions of S. salivarius genomic DNA, extracted from Ruddy and White solutions. Triangles: Red solution; Circles: Edward White solution. Error bars represent standard divergence

The results from "in field" analyses are rumored in Table 2. All the samples correctly sterilized afterward allover reprocessing resulted clear negative for Mix_S, as symptomless American Samoa for all the other Veridical Time PCR Mix.

Out of the 22 "in field" used os mirrors, the Mix_S was able to detect either S. salivarius and S. mutans in 77 %. Only three samples tested positive with the Mix_ES, and one of them was positive for Enterococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus. All the samples were negative at the Mix V.

Thomas More than half (60 %) of the bone mirrors immersed in the disinfectant bowl were still found to beryllium positive for the Mix_S. However, the remaining 40 % of disadvantageous samples were already at a very low level of contamination after use (Ct >35) and exclusively single pillow slip testing perverse after role became positive (CT = 27.7) after immersion in the disinfection bowl (sample 4d, see Defer 2). In only three cases, the samples were positive for Streptococcus mutans, while one sample was affirmative at the Mix_ES, and with a double positivity both for E. faecalis and S.aureus Also in this set of the experiment, the samples were all negative for the Mix V.

The samples collected from the temporary storage bowl (n = 8) were altogether negative for Mix_ES and Mix_V; but ane sample proven positive for some bacterium noticeable away Mix_S, suggesting a possible sporadic taint of the storage bowl.

91 % of the 11 swabs contaminated directly with salivary fluid from human volunteers tested positive with Mix_S, and negative with the other Mix.

As far-off A the imperfect DNA tests are afraid, a selection (n = 20) of borderline samples was tried and true confirming that 19 contaminated and/or disinfected mirrors showed the mien of human DNA in the range 0.02–0.36 nanogram/μl (data non shown). Only unitary sample distribution (20u) time-tested negative for both mfDNA and human DNA.

Consistently, all the sterilized mirrors were also negative for the presence of quality DNA.

Supported on the observed results, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, false sensationalism rate, mistaken negative rate, efficiency and selectivity of the tests. As shown in Put of 3, the results were respectively 81 %, 100 %, 0 %, 2, 82 % and −0.11 for "in field" samples when using the raw data (referring to the whole monitoring procedure: sampling-extraction-analysis), and 95 %, 100 %, 0 %, 0.5, 95 % and −0.05 after substantiation of false negative results (referring only to the analysis by a real time gain method); while for dental mirrors experimentally contaminated with artificial secretion solutions, we obtained the same values for specificity, false positive grade, simulated destructive plac, and selectivity, but observed a further increase in sensitiveness (100 %) and efficiency (100 %). Taken conjointly, these data living the effectiveness of the projected approach.

Discussion

Increasing knowledge on cross-infection risks in os health care [6, 12–18] has led to cleared surveillance procedures in dental hygienics practice in the last years. Starting from the 1980s, CDC and other agencies have publicized and updated taxon guidelines for reusable instruments, focusing on the cleaning/disinfection/sterilization flow and on the necessitate for effectuality and appropriateness, to obtain a "step by stone's throw" trustworthy sanitation communications protocol [12, 18–20]. Implementing the monitoring of sanitization procedures for reprocessing learned profession devices plays a fundamental frequency role in assuring safety and preventing healthcare-associated infections.

We tested the applications programme of a new molecular approach, founded on the identification of residual traces of a natural fluid starting from the detection of its microflora components away mfDNA gain. In comparison to tralatitious protocols based connected bacterium indicators, this strategy requires an equipped building block biology laboratory, but seems to carry several advantages. Firstly, it is main of microbial culture requirements, allowing the detection of traces even after fractional or unsuccessful reprocessing. Secondly, it is not based on pathogen recognition, but on the search for microbial markers whose presence in begotten fluids would indicate a possible occurrence of undesirable pathogens, including viruses OR prions, gum olibanum suggesting a failure in the reprocessing chain. Furthermore, the method settled connected bacterial DNA amplification has the advantage of starting from prokaryotic cells, that are in higher number in saliva in equivalence to tissue exfoliated human cells and have a higher DNA resistance to environmental agents. In the end, the spit microbial key signature can be easy enforced supported on microbiome achievements and technical advances, representing a promising approach to monitoring sanitation procedures. In comparability to longstanding culture supported methods, the main limits of this strategy admit the availability of a molecular biology science laborator well-found with a real meter PCR setup, with agnatic costs; moreover, it is not possible to discriminate between live and dead cells; finally, not all the different steps can comprise evaluated, such as autoclaving performance or partial disinfection. However, IT is important to look at that sterilisation controls and antimicrobic evaluation are already fine established following mandatory rules [18–20].

We searched for residuum salivary traces by mfDNA analytic thinking, in put to value the extent of sanitisation of reprocessed dental devices, collected after different treatments. For this purpose, we performed two kinds of evaluation: the Experimental test, based on trials carried out along dental mirrors, experimentally contaminated by two different artificial salivary solutions; and the "In line of business" tryout, performed connected dental mirrors actually in use in casual alveolar care settings. The main final result concerns the demonstration of the feasibility of MFDNA analysis arsenic a tool for monitoring sanitation efficacy in reprocessing dental instruments.

In the Experimental test, all the contaminated or partially sanitised samples time-tested positive for the presence of saliva traces, and merely the completely processed samples were confirmed as disconfirming. This result suggests that saliva traces, heard by amplification of MFDNA, can really act a useful marker for monitoring sanitation. Moreover, the contamination was also identified in samples that were autoclaved without the compulsory cleaning and disinfection stairs, further confirming its applicability in surveillance.

Replete disinfection and appropriate cleanup represent the fundamental steps for saliva removal, following guidelines [18–20]. The somatogenetic or chemic sterilization footstep is substantial to avoid further contaminations related or not to biological fluids, as well as to safely package and store the reprocessed medical tools [19].

The bacterial genome has a high environmental resistance to chemical and corporal stressful conditions. This resistance could sham the differences betwixt full and shorter treatments both for Red and White solutions (Table 1). Data reported in Shelve 1 show some variability in experiments conducted with Bolshie resolution, compared to those performed with White solution, all the same these differences were not statistically significant.

Interestingly, straight-grained after disinfection or autoclave handling, both white and red solutions were detectable, showing that no amplification inhibition of artificial saliva was induced by hemoglobin or proteins operating theater bactericidal residues, neither after heating system or drying steps.

However, it should be emphasized that experimental results were obtained under a controlled situation, without interferences, such as the presence of other microorganisms, environmental agents and using an established load of S. salivarius. For this cause, we also applied the "in plain" strategy considering several situations in a blind sample collection. The projected approach was successful also when exploited for "in field" assays, confirming the sanitization of the mirrors correctly reprocessed, and conversely showing the presence of secretion fluid on samples used and not treated, or used but partially or inappropriately processed.

In the "in airfield" test, we reported a slight reduction in sensibility and efficiency, mainly out-of-pocket to false negatives resulting from used and non sanitized mirrors. In decree to confirm this data we verified samples for the presence of amplifiable DNA, including humanlike spit traces and cultivable bacterium, excluding repressive effects or laboratory hybridisation contaminations. Finally, only one sample out of a total of five proved to be a confessedly false negative; since the mirror was used, DNA was gift, human DNA was revealed, but saliva mfDNA was never perceived. Another sample, indeed, had no DNA, probably imputable a failure in sampling or in the extraction phase or because the mirror was non in contact enough and polluted with saliva. The other three samples showed a relevant preconception in the microflora structure since they were collected from patients affected by Candidiasis, suggesting that Candida colonization (or the do drugs treatment) may have interfered with the levels of S. salivarius in spittle. Even if commensal existence of buccal Candida species is not a rare condition [28], its concentration was usually much lower berth (three folds) than those recovered in these false negative samples. The opening that a pathology operating theatre antibiotics English hawthorn intervene with this mfDNA-based approach was already considered in forensics applications [29]. This limitation might be easily overcome away increasing the number of samples when monitoring a carping surveillance appendage. Moreover, the extension of the panel of oral bacteria markers, potty promote overcome this limit, enhancing the already high level of sensibility.

The effectiveness of the unspecialized principle based along tracing saliva aside mfDNA analysis was highlighted by the consistent negativeness shown when exploitation other PCR Mix self-addressed to the identification of other biological fluids (e.g. vaginal and colonic). The sporadic (4 out of 83) observed low positivity for S. aureus Oregon Enterococcus spp. in saliva hind end live due to accidental contamination, rare merely possible [30].

In unremarkable hospital practice, common disinfection bowls can temporarily join different medical checkup devices, just afterward their use. When the method acting was applied to dental mirrors immersed in this container, a possibility of thwartwise pollution emerged, as confirmed also by mop samples collected from the arena liquid OR surfaces, showing positivity for bacterium detectable by Mix_S. Saliva residuals were recovered some on dental mirrors disinfected surgery antiseptic without explorative cleaning and disinfection. The latter remarks are in accordance with several reports and far highlight the need for succeeding each the required sanitisation steps, American Samoa advisable in the specific guidelines [6, 14, 18–20]. This is a critical point that can also be master by the mfDNA monitoring [5]. Additional questions May arise for new pathogens Oregon prion proteins that are invisible by neoclassical methods Oregon could be more insubordinate to sanitation. This is especially relevant when the infected biological fluids are dried on the glass surgery auriferous surfaces of reusable tools, and/or would have only partial reprocessing [31]. Conventional methods supported microbial culture or single pathogen detecting cannot be applied to monitor nigh of these events. Molecular tracing of biological fluids May overcome some of these limits related to feasible but not cultivable species operating theater referable the detection of microorganisms later on disinfection treatments.

Limitations of the method acting

The lack of a highly sensitive and specific gold standard to metre 'perfect sanitation' represented a main limitation to compare the effectiveness of the proposed method. Despite the miss of an optimal reference epitome, we approached validation using definitive microbiology, as traditionally performed in routine surveillance. Moreover, since risks related to incomplete sanitation are healthcare-associated infections, the detection of growing bacteria always is a primal test for hospitals practice and guidelines [12, 18, 20].

Other limitations of the proposed method include the availability of an equipped molecular biology science laborator and trained personnel department. If reagents and consumables for real time PCR are readily available, to lay up of a new laboratory would require relevant efforts and costs. However, most hospitals already have available real time pcr instruments for routine diagnostics. Finally, a major restriction of the method is related to the presence of dismicrobisms. Antibiotics, inflammatory diseases, oral disinfectants OR even acute infections (e.g. Candidosis) may dramatically change the microflora biodiversity, resultant in possible false negatives. However, considering the high sensitiveness (>80–95 %), sampling of reusable devices connected a large exfoliation may overcome this limitations and support surveillance programs.

Conclusion

The general principle of detecting residual spittle by microflora DNA amplification further shows the multifaceted complexness of monitoring the reprocessing process. The proposed approach supported tracing biological fluids by mfDNA seems to represent a auspicious model and a executable resolution for infection control and prevention in bone health care or opposite infirmary settings.

Abbreviations

CDC, centers for disease control and prevention; CFU, colony forming units; CT, cycle threshold; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; HAIs, health care-associated infections; mfDNA, microflora DNA; Real-time PCR, tangible-time polymerase chain reaction

References

- 1.

World Health Organization. Report on the burden of endemic healthcare-associated infection worldwide. A nonrandom review of the lit. Holland gin: WHO Press; 2010.

- 2.

WHO. Health-care associated infection. Fact Shrou. Geneva: WHO Press; 2014.

- 3.

Cristina Milliliter, Spagnolo AM, Sartini M, Dallera M, Ottria G, Perdelli F, et al. Investigation of structure and hygiene features in dentistry: a pilot take. J Prev Med Hyg. 2011;50:175–80.

- 4.

Manfredi R. Activity exposure and prevention guidelines in medicine and stomatological settings—a literature review. Infect. 2010;14:68–83.

- 5.

Szymańska J. Microbiological risk factors in dentistry. Current status of cognition. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2005;12:157–63.

- 6.

Smith G, Smith A. Microbial contamination of used medicine handpieces. Am J Taint Control. 2014;201442:1019–21.

- 7.

Mahboobi N, Agha-Hosseini F, Mahboobi N, Safari S, Lavanchy D, Alavian MS. Hepatitis B virus infection in dentistry: a forgotten topic. J Microorganism Hepat. 2010;17:307–16.

- 8.

Lodi G, Porter Sr, Teo CG, Scully C. Prevalence of HCV infection in health guardianship workers of a UK alveolar hospital. Br Ding J. 1997;183:329–32.

- 9.

Perry JL, Pearson RD, Jagger J. Infected wellness care workers and patient of safety: a double standard. Am J Infect Control. 2006;34:313–9.

- 10.

Ahtone J, Goodman RA. Serum hepatitis and alveolar personnel: transmitting to patients and prevention issues. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;106:219–22.

- 11.

Laheij AMGA, Kistler JO, Belibasakis GN, Välimaa H, de Soet JJ, European Oral Microbiology Workshop (EOMW) 2011. Health care-associated microorganism and bacterial infections in odontology. J Rima Microbiol. 2012;4:17659.

- 12.

Kohn WG, Wilkie Collins AS, Cleveland JL, Harte JA, Eklund KJ, Malvitz DM. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Guidelines for transmission control in alveolar health-care settings—2003. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–61.

- 13.

Shah R, Collins JM, Hodge TM, Laing Erbium. A home study of cross infection ascertain: 'are we clean enough?'. Br Dent J. 2009;207:267–74.

- 14.

Bhandary N, Desai A, Shetty YB. High speed handpieces. J Int Buccal Wellness. 2014;6:130–2.

- 15.

Dallolio L, Scuderi A, Rini MS, Valente S, Farruggia P, Sabattini MA, et alibi. Effect of different disinfection protocols on microbial and biofilm contaminant of dental unit waterlines in community dental practices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:2064–76.

- 16.

Bagg J, Joseph Smith AJ, Hurrell D, McHugh S, Irvine G. Pre-sterilisation cleanup of Re-usable instruments in unspecialised dental practice. Br Dent J. 2007;202:E22.

- 17.

Moradi Khanghahi B, Jamali Z, Pournaghi Azar F, Naghavi Behzad M, Azami-Aghdash S. Knowledge, attitude, recitation, and position of infection control among iranian dentists and medical specialty students: a systematised review. J Gouge Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2013;7:55–60.

- 18.

Rutala WA, Weber DJ. The Health care Infection Control Practices Consultive Committee (HICPAC). Guideline for Disinfection and Sterilization in Healthcare Facilities, 2008. Available on hypertext transfer protocol://web.CDC.gov/hicpac/Disinfection_Sterilization/acknowledg.html. Accessed June 2016.

- 19.

Department of Health, England. HTM 01–05: Decontamination in primary care dental practices. 2013 Version Leeds. Useable on https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/decontamination-in-primary-care-dental-practices. Accessed 4 Aug 2016.

- 20.

Centers for Disease Control and Bar. Guidelines for infection control in dental wellness-care settings—2003. MMWR. 2003;52:RR–17.

- 21.

Law JW, Ab Mutalib NS, Chan KG, Lee LH. Rapid methods for the sleuthing of foodborne bacterial pathogens: principles, applications, advantages and limitations. Front Microbiol. 2015;5:770.

- 22.

Valeriani F, Giampaoli S, Buggiotti L, Gianfranceschi G, Romano SV. Molecular enrichment for detection of S. aureus in recreational waters. Water Sci Technol. 2012;66:2305–10.

- 23.

Giampaoli S, Berti A, Valeriani F, Gianfranceschi G, Piccolella A, Buggiotti L, et Camellia State. Molecular identification of canal fluid by microbial signature. Rhetorical Sci Int Genet. 2012;6:559–64.

- 24.

Giampaoli S, Alessandrini F, Berti A, Ripani L, Choi A, Crab R, et al. Forensic interlaboratory evaluation of the ForFLUID kit for vaginal fluids identification. J Rhetorical Leg Med. 2014;21:60–3.

- 25.

ISO 18593:2004. Specifies horizontal methods for sample distribution techniques using link plates or swabs on surfaces in the food for thought industry environment (and nutrient processing plants), with a view of detecting or enumerating viable microorganisms. 2004. Usable at web.iso.org/iso/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=39849.

- 26.

Nadkarni MA, Martin Atomic number 26, Jacques NA, Hunter N. Determination of bacterial load by time period PCR using a broad-range (general) probe and primers set. Microbiology. 2002;148:257–66.

- 27.

Yano A, Kaneko N, Ida H, Yamaguchi T, Hanada N. Time period PCR for quantification of Streptococci mutans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217(1):23–30.

- 28.

Zaremba Mil, Daniluk T, Rozkiewicz D, Cylwik-Rokicka D, Kierklo A, Tokajuk G, et alibi. Incidence value of Candida species in the oral cavity of old and aged subjects. Adv Med Sci. 2006;51:233–6.

- 29.

Choi A, Shin KJ, Yang WI, Lee HY. Body fluid identification by integrated analysis of DNA methylation and torso runny-specific microorganism DNA. Int J Legal MEd. 2014;128:33–41.

- 30.

Wang QQ, Zhang Pancreatic fibrosis, Chu CH, Zhu XF. Prevalence of Enterococcus faecalis insaliva and occupied source canals of teeth associated with top periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2012;4(1):19–23.

- 31.

Azarpazhooh A, Fillery Male erecticle dysfunction. Prion disease: the implications for dental medicine. J Endod. 2008;34:1158–66.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Maurizio Anselmi for technical support and Dr. Elena Scaramucci for bibliographic updating.

Funding

Supported by grant IUSM n. 81/2011.

Availableness of information and materials

Data for this manuscript as well as additional information on all materials used in this study are on tap upon petition from the like source.

Authors' contributions

FV was involved in the design of the inquiry, performing experiments and writing the paper. CP performed statistical analysis and collaborated in writing the paper. GG contributed to experiments and the acquisition of data. PC, VC and GL were caught up in sampling collection and planning. MV, MD and VRS designed the study, supervised research and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they own no more competing interests. VRS collaborated with the MDD University Spin Inactive holding patent lotion WO2012117431A1 for identification of biological fluids in forensics.

Consent for publication

Non practical.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The analyze communications protocol was submitted to the Individual Ethics Commission and authorized. All human participants included in the study provided consent to participate.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits open employment, distribution, and reproduction in any sensitive, provided you give congruent credit to the daring author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Productive Commons license, and suggest if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zipp/1.0/) applies to the information made available in that article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Valeriani, F., Protano, C., Gianfranceschi, G. et al. Infection control in healthcare settings: perspectives for mfDNA depth psychology in monitoring sanitation procedures. BMC Infect Dis 16, 394 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1714-9

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1714-9

Keywords

- Healthcare-related to infections

- Dental health care

- mfDNA

- Real metre PCR

- Sanitation procedures

- Surveillance

the effectiveness of sanitation procedures in hospitals is determined

Source: https://bmcinfectdis.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12879-016-1714-9

Posting Komentar untuk "the effectiveness of sanitation procedures in hospitals is determined"